Good sportsmanship is important, regardless of what specific activity you have chosen to compete in. Child or adult, male or female, team sport or individual, shaking hands and saying, “Good job” should always be part of the experience. Some people compete differently than others, and respecting another person’s process is part of sportsmanship as well, but when the match concludes, being able to treat others how you would like to be treated is just as much a part of sport as throwing far, jumping high, or scoring lots of points.

This year, 2019, will be my 18th overall season as a javelin thrower. I’ve competed with all kinds of individuals. I can’t pretend that I’m the perfect competitor, and likely that doesn’t exist, as I’m sure any behavior can be subjectively perceived by somebody as not ideal. But I’m here to tell you that athletes in individual sports can and should be friends! Especially in the field events within track and field.

Mostly, I think throwers already have this down. I have formed wonderful friendships through teammates and competitors alike, but the negative experiences have also been pretty darn negative, so I think it’s a worthwhile conversation. If you can strike the balance of doing what you need to do to perform well and also support your fellow athlete, you’re succeeding! I promise it’s possible to do both.

Two big reasons you can be friends in field events, and if you’re not friends, you should at least be sportsmanlike:

1. You have no effect on someone else’s performance.

2. You’ve all chosen to do this niche, weird thing. You probably have stuff in common.

Let’s start with the first one. Individual sports are either combative or not. Wrestlers, fencers, judo athletes and boxers literally fight each other to see who wins. Divers, gymnasts, jumpers and throwers take turns performing, and scores or distances decide the victor. In an individual, non-combative sport, there is nothing you can do to change someone else’s outcome: You only control your own destiny. Knowing that, focusing on it, and relying on your own strengths and talents is how you win. Then, having enough confidence in your own process that you can genuinely support others’ efforts can be really empowering.

At a basic level, yes, you have no effect on someone else’s outcome. If you aren’t nice, though, just know that a strong competitor will beat you anyway. Almost nothing fires me up more than someone being unnecessarily rude within a competition, and my track record in rising above that behavior with far throws is almost flawless (and luckily, it doesn’t happen that often). In the other, happier direction, cheering others on can make a big difference in certain situations.

Barbora Špotáková told me a really neat story a few years ago about the Beijing 2008 Olympic Final. A Russian, who has since been stripped of her silver medal, was leading the competition. It came down to the sixth and final round, and Barbora was in silver medal position. The last two people to throw would be Barbora and that current Russian leader. She was nervous, she said she didn’t know if she could do it (pass the leader), and suddenly a few other women who had been her top competitors for years and years encouraged her. They told her that they believed, and Barbora threw 71.42m to win her first Olympic Gold. I’ve sung my friend Barbora’s praises many times, but this story of many other competitors lifting her up when she needed it (and, I would argue, when the sport needed it) speaks volumes of her as a sportsmanlike, strong competitor. Those other women had done their best and focused on their own outcome to that point, but also saw the role that they could play in empowering Barbora, who had it within her to win, in that moment.

Cheering people on within competition isn’t something that really has to happen. Because in the same way that you’re in charge of your performance, so is everyone else! It’s not your responsibility to cheer others on, it just can be your privilege. Another way to be a supportive presence in the course of a meet is simply staying in your own lane. Everyone has their own process, whether that’s blasting metal through headphones, napping in the warm-up area, being chatty, or appearing moody but maybe just being focused on the task at hand. Respect others’ processes. Don’t bound up to a quiet person and demand conversation. Put your own headphones or earplugs in if someone’s loud music starts to bother you. Find your own quiet corner to lay down between throws if you need to. Let others do as they will, and focus on your own job while they do the same. Everyone is different, and there isn’t one right way to be.

It's true that everyone is different, but you also are all doing the same thing. Point number 2 is that perhaps you have more in common with your competitors than you think! And common ground is a basis for friendship.

It would be difficult to forge a full-fledged Friendship on the javelin runway in the midst of competition, but hints of one might begin there. Being a respectful competitor can open the door for conversation and camaraderie off the runway, though, and you might be surprised by just how much you have in common with and like your fellow throwers.

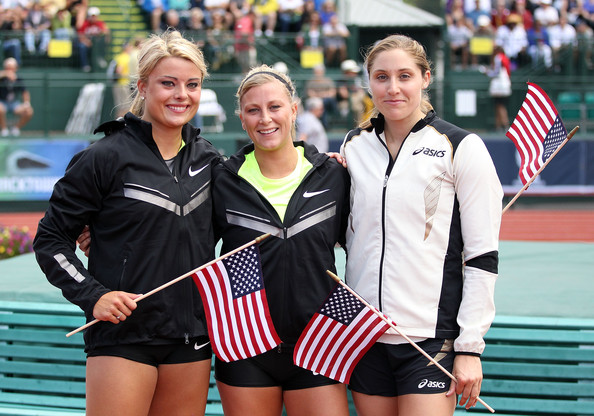

I first (very briefly) met Dana at the 2004 Olympic Trials, where she did well and I was 19th out of 21 competitors. We threw against each other again in April of the next year at Cal Berkeley, where I threw 52 meters for the first time, in large part due to inspiration by Dana (who won). We met again at NACAC U-23 Championships in July of 2006 in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, where she won in dominating fashion and I was seventh. We had an absolute blast with Britney Henry, Russ, Adam Kuehl, and everyone else amazing on that trip. Would I have become life-long friends with and a happy wife to these people if I had sulked about my performance? No. They’re some of the most important ones in my life, and now Dana is my fantastic, fun coach. I love that we became friends through our competitive years and are now making dreams come true together.

Photos above are 12 years apart: Dominican Republic to Vail, CO! <3

In 2012, during warm-ups for the final of the Olympic Trials, Dana had everyone get together for a group photo (it was her last Olympic Trials). In this photo, Ari and I stood right next to each other. We didn’t really speak again for five years. Then, at a meet at IMG Academy in 2017, she, Maggie Malone and I were roommates and the only elite javelin throwers in attendance. We decided to help each other out in competition as no one’s coach had come, Ari PRed and made her first world team later that summer, we swam in the ocean, and it became clear really quickly that we were meant to be Friends! I’m visiting her in Houston this week, training together and watching Kimmy Schmidt. If we took ourselves too seriously as javelin throwers, we would have missed out on a friendship that I treasure dearly. We met throwing the javelin, but we’ve bonded over a lot of other things! And friendship will last longer than javelin.

Maybe you have friendship potential with competitors that you haven’t recognized yet. Friendship will last longer than any sport, not just specifically javelin. Sportsmanlike behavior, in my opinion, is much easier than the opposite. In my experience, being closed off, nervous, and protective of your own space is more difficult than just relaxing within a competition. Trying to take myself really seriously has always resulted in tightness and disappointment, and that’s a trap I’m trying my hardest not to fall into anymore at the biggest meets each season. Dana accompanying me to Zurich in 2018 was huge for keeping me relaxed and having fun when it mattered the most.

Post-2018 Diamond League Final, happy in the stands!

That last idea leads me to answering a question I got on Instagram:

Q: In high school I always felt judged and nervous at a meet, how do I fix that for college?

A: You’re nervous because you care about the outcome! I still get nervous, because I want to do well, and represent those who believe in me to the best of my ability. Being able to handle nerves, though, comes down to knowing that you did everything in your power to be ready for the opportunity that you’re facing. Focus in on a few cues that have worked really well for you leading into competition, and only worry about executing those. Having objective goals and knowing you have developed the tools to achieve them through hard work helps relax you, and then far throws can happen!

Perceived judgement is a little bit of a different thing. 1) If you think competitors are judging you, stop that right now. It’s not your job to worry about what they’re thinking, and likely they’re too worried about their own job to give you a second thought! Only worry about what you can control, and others’ thoughts don’t belong in that category. This takes practice but is such a valuable mental tool! 2) I used to get really worked up about the crowd watching too, so if spectators’ attention is what makes you feel judged, I get you! The thing that I came to realize, though, is that people are watching because they want to be wowed. Spectators are there because they want to see something amazing happen!! So their attention is always positive. Focus on that and hopefully you’ll grow to feel their presence and cheers as support rather than pressure. I’d love to hear how it goes!